London in the eighteenth century was noisy, smoky and crowded. Coffee houses were packed with merchants, lawyers and speculators arguing over ships, wars and money.

At one of those cramped wooden tables, a group of men in wigs pass around a document with a stranger’s name on it.

They have never met this person.

They are not family.

They are not friends.

If that person dies within a set period, they get paid. If the person lives, they lose their money.

It is a life insurance policy.

This strange world of “death bets” is not just a dark historical footnote. It is the reason modern life insurance, insurance law, underwriting, actuarial science, legal liability and the idea of a policy beneficiary look the way they do today.

When Life Insurance Was A Legal Death Bet

Today, a life insurance policy is sold as protection. You pay premiums, and if you die, your family or chosen beneficiary gets money. The idea is that they have an insurable interest in your life. They suffer a real financial loss if you are gone.

In the early eighteenth century, the law did not clearly demand that.

If an insurance office agreed, a stranger could buy a policy on your life simply because you looked fragile, important or unlucky. Life insurance could function like a legalised bet on your death.

Speculators would:

- Pick a visible target: a politician, a bishop, a wealthy older landowner, an admiral about to sail.

- Study rumours and visible health problems.

- Pay premiums on a life insurance policy that would pay out if that person died before the policy expired.

If the person died in time, the speculator filed an insurance claim and collected the money. If not, the premiums were lost. Lives became numbers on paper and death turned into a financial event.

Fun facts from the death bet era

- It was possible to hold multiple policies on the same famous person, like building a portfolio of human “assets.”

- Some investors treated life policies the way others treated lottery tickets, buying small stakes on several different lives.

- Critics complained that this twisted the meaning of insurance from “protection against loss” into “hoping for loss.”

Coffee Houses And High Risk Lives

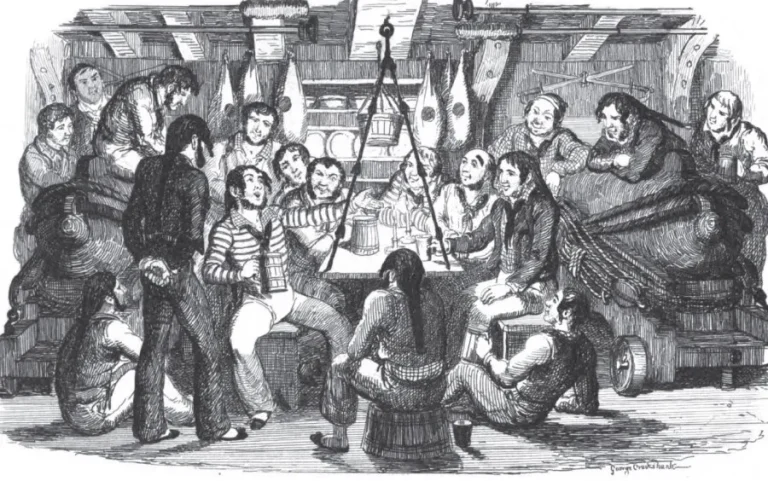

To see this culture in action, you would not go to a casino. You would go to a London coffee house.

These places were the social media and trading floors of their day. News of wars, shipwrecks, elections and illnesses travelled from table to table.

They also became informal centres for life insurance speculation and high risk liability.

Inside, you might find:

- Groups pooling money to buy life insurance policies on a single public figure.

- Messengers running between coffee houses and insurance offices with new proposals.

- Heated arguments about whose life was “worth backing” based on gossip, appearances and recent behaviour.

A single cough in public, a rumour of illness or a dangerous journey announced in the papers could trigger a wave of policies on that person’s life. The line between conversation and financial risk assessment was thin.

Fun facts from the coffee house floor

- Some coffee houses became known for insurance business, attracting underwriters, attorneys and speculators alongside merchants.

- People watched famous figures in theatres and churches partly as entertainment, partly as real-time health checks on their “investments.”

- A person’s reputation for drinking, duelling or dangerous travel could directly change how attractive their life was as a bet.

Guesswork Underwriting And The Rise Of Actuarial Science

Modern life insurance uses underwriting and actuarial science. Insurance underwriters and actuaries study age, medical history, job risks and statistics to decide how likely you are to die within a certain period. They set your premiums based on mathematical risk assessment.

In the eighteenth century, none of that was standardised.

Underwriters had to rely on:

- Church burial records and basic population statistics.

- A person’s estimated age and occupation.

- A quick visual inspection and a short conversation.

There was little understanding of many diseases. No blood tests, scans or advanced diagnostics. Yet these decisions still created serious legal liability for insurers. If too many insured people died too quickly, companies could go bankrupt. If they refused to pay, they faced court cases for breach of contract.

To survive, insurers had to improve their methods. Over time, they developed more systematic tables of life expectancy and began to build the foundations of actuarial science.

Disputes over claims also encouraged clear rules about honesty:

- People who hid major illnesses or lied about their lifestyle could be accused of material misrepresentation.

- Insurers sought a contestable period in which they could investigate suspicious claims before accepting permanent liability.

- Courts pushed both sides towards a duty of clear disclosure and fair dealing.

Fun facts from the early underwriting trenches

- An underwriter could assess you by watching how you walked into the room and listening to you speak for a few minutes. That was their medical examination.

- Occupations like soldier, sailor and miner were classified as dangerous, but speculators often preferred them because the chance of a quick payout was higher.

- Underwriting mistakes became public scandals when insurance offices collapsed under the weight of too many successful claims.

From Death Bets To Law: The Life Assurance Act 1774

As death betting grew, so did unease. People saw that a life insurance policy was not always a tool of protection. Sometimes it was a weapon of temptation.

If a person stood to gain a lot of money from another’s death, questions naturally followed:

- Would they delay calling a doctor.

- Would they push for risky decisions.

- Could life insurance become a motive for crime.

Courts were soon flooded with messy cases over disputed claims. Judges had to decide whether some life insurance policies were really just wagers in disguise.

The result was the Life Assurance Act 1774.

This act changed everything:

- It required an insurable interest in the life being insured. You had to show a legitimate financial or relational connection to the person.

- It made clear that policies taken out purely as speculative bets could be treated as void.

- It reinforced the principle of indemnity: insurance should protect against financial loss, not create profit from misfortune.

A policy beneficiary was expected to be someone who would be worse off financially if the insured person died, not someone who simply guessed they might.

The act gave courts a tool to reject the most blatant death bets, while allowing genuine family and business protection to continue. It helped transform life insurance from gambling instrument to regulated financial product. The same fear of professional mistakes that shaped insurance law also transformed medicine itself. If you want to see how early rulers punished bad doctors, read our deep dive into the history of medical malpractice from Hammurabi’s Code to modern law.

Fun facts from the legal turning point

- Some speculators rushed to sign policies before the act took effect, hoping to squeeze in a few more risky bets.

- The phrase “insurable interest” became a key part of insurance law, shaping who can legally benefit from a life insurance policy.

- The act is still cited in modern cases involving suspicious policies and disputed beneficiaries.

18th Century Death Bets vs Modern Insurance

The strange practices of eighteenth century London have modern echoes in today’s insurance and legal world.

| 18th Century Practice | Modern Insurance / Legal Concept | What Changed |

|---|---|---|

| Death bets on strangers | Insurable interest | Beneficiaries must have a real financial stake. |

| Coffee house gossip on lives | Actuarial risk assessment | Data and statistics replaced rumour and guesswork. |

| Visual health checks | Medical underwriting | Formal health questions, exams and medical records. |

| Disputed payouts | Insurance litigation and legal liability | Courts use clear rules on fraud and contract terms. |

| Hidden illnesses | Material misrepresentation rules | Lies can void a policy or deny a claim. |

| Sudden waves of claims | Professional indemnity and solvency rules | Regulators and actuaries try to keep insurers stable. |

The table looks like a neat comparison, but every row represents real people, real money and real court battles that forced the system to change.

Why This Strange History Still Affects Your Policy Today

When you see modern terms like life insurance quote, policy beneficiary, underwriting, contestable period or legal liability, you are looking at the cleaned up remains of a chaotic past.

Many familiar features of life insurance exist because of those early problems:

- Forms ask what your relationship is to the insured person to prove insurable interest.

- Health questions and medical checks are used to manage risk and prevent material misrepresentation.

- Policy wording spells out the insurer’s liability and the circumstances under which a claim can be denied.

Other areas of law have been shaped by similar pressures:

- Medical malpractice cases examine when a doctor’s action or inaction causes harm and who is financially responsible.

- Professional indemnity insurance protects lawyers, doctors, accountants and advisers from claims that their mistakes caused loss.

- Maritime insurance and maritime law grew alongside life insurance as traders tried to manage the risks of shipwrecks, storms and fraud.

The morbid death bets of the eighteenth century forced society to ask how far it was willing to go in turning human lives into financial instruments. The answer, written into law, still controls how life insurance works today. Long before life insurance policies and indemnity clauses, early medieval kings were already putting cash values on human bodies. To see how a lost thumb or smashed jaw turned into a fixed payout, read our article on the history of personal injury law and Anglo-Saxon wergild.

Quick Glossary Of Morbid Insurance Terms

Life insurance policy

A contract in which an insurer promises to pay a sum of money when the insured person dies, usually to a named beneficiary, in exchange for regular premiums.

Policy beneficiary

The person or organisation entitled to receive the payout from a life insurance claim.

Insurable interest

A legal requirement that the policyholder must suffer a genuine financial loss if the insured person dies. It prevents pure gambling on strangers’ lives.

Premiums

The payments made to keep an insurance policy active. They can be monthly, yearly or in a single lump sum.

Underwriting

The process insurers use to decide how risky a person is to insure and what premiums to charge.

Actuarial science

The application of mathematics and statistics to assess risk and calculate insurance and pension obligations.

Legal liability

Responsibility recognised by law. In insurance, this includes an insurer’s duty to honour valid policies and pay legitimate claims.

Contestable period

A time frame, usually during the first years of a life insurance policy, when the insurer can investigate and deny a claim if they find fraud or serious misrepresentation.

Material misrepresentation

A false statement or hidden fact that would have affected the insurer’s decision to issue the policy or set the premiums.

Principle of indemnity

The idea that insurance should compensate for actual financial loss, not create a profit from a claim.

Professional indemnity insurance

Cover that protects professionals such as doctors, lawyers or financial advisers if a client claims their mistake caused financial or physical harm.

Yes. Before rules about insurable interest were tightened, a person could buy a life insurance policy on someone they did not know, if an insurer agreed. This turned life insurance into a kind of regulated bet on death and helped trigger later reforms in insurance law.

Modern law makes direct betting on a stranger’s life much harder, but debates continue around stranger originated life insurance and complex financial products linked to mortality. Regulators, insurers and courts still watch for arrangements that look too much like the old death bets in new clothing.

Because early underwriters relied on guesswork, many insurers mispriced risk and suffered heavy losses. Over time, they turned to more systematic data and calculation. This pressure helped create actuarial science, modern underwriting practices and the use of statistics to manage long term liabilities.

Detailed questions about health, occupation and habits help underwriters assess risk fairly and protect insurers during the contestable period. They also reduce the chance of material misrepresentation, which can cause a claim to be denied or a policy to be cancelled.

Modern law makes direct betting on a stranger’s life much harder, but debates continue around stranger originated life insurance and complex financial products linked to mortality. Regulators, insurers and courts still watch for arrangements that look too much like the old death bets in new clothing.