Key Facts (The “Too Long; Didn’t Read” Version)

- The first specialist: Nicholas Barbon’s Fire Office (1680) was London’s first dedicated fire insurance company.

- The scale: The Great Fire of 1666 destroyed around 13,200 houses, roughly 80% of the City.

- The insurance pivot: Nicholas Barbon helped turn urban disaster into a measurable, insurable business risk.

- The fire mark twist: If your house didn’t show the right metal plaque, you could slip to the bottom of the priority list when the fire engines arrived.

London Wakes Up on Fire

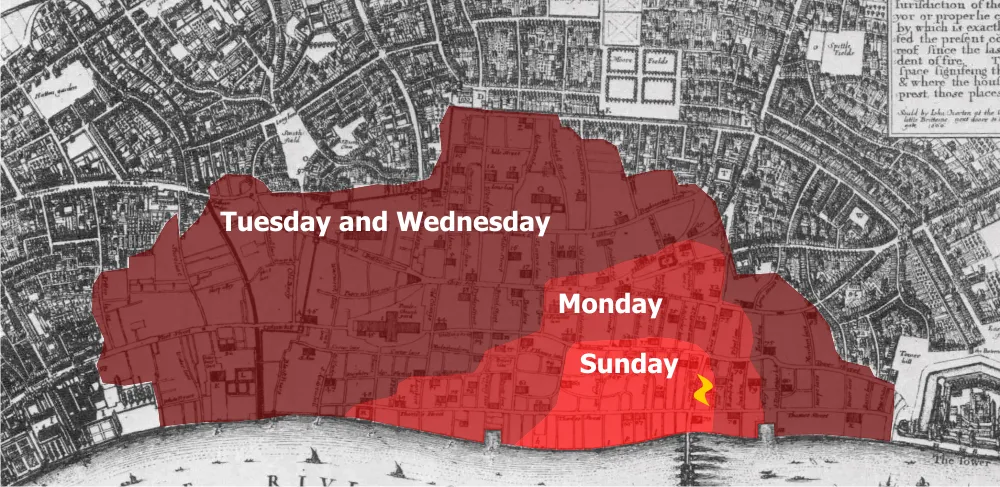

Just after 1 a.m. on Sunday 2 September 1666, a baker in Pudding Lane finished work, banked his oven, and went to bed. By breakfast, London was a furnace.

Timber houses went up like matchsticks. Roofs caved in. People ran into the streets half dressed, dragging trunks, children, and whatever they could carry. The heat was so intense that the lead roof of St Paul’s Cathedral melted and flowed into the streets.

Four days later, when the flames finally died, about 13,200 houses were gone. The medieval city was a smoking grid of foundations.

And if your house was one of those blackened shells, that was it. No claim number. No helpline. No “we’re processing your payout.” In 1666, your insurance plan was “hope the King feels sorry for you.”

Charles II did try. He ordered church collections across the country and raised about £16,400. The estimated damage bill was around £10 million. That is roughly a 0.13 percent recovery rate.

Charity was not going to rebuild a capital city. London needed something new: a way to turn catastrophe into numbers and contracts instead of prayers and panic.

1. Before the Fire, Insurance Didn’t Exist (Seriously)

In seventeenth century London, fire was officially an “Act of God.” Legally and financially, that was a shrug.

If lightning hit your roof, or your neighbour’s chimney threw sparks onto your thatch, you were just unlucky. There was no standard system for sharing the risk. Wealthy people might own several properties to spread their chances. Everyone else crossed their fingers.

After the Great Fire, that attitude suddenly looked reckless. The City’s merchants could see the problem clearly: one bad night in Pudding Lane had wiped out homes, workshops, warehouses, and rental income across the whole commercial district. Charity wasn’t a scalable business model for a global trade hub. London needed to turn catastrophe into math. This shift from “divine punishment” to “calculable risk” is the foundation of every policy you pay for today and sits in the same long tradition as early compensation systems like Anglo Saxon wergild, where even injuries and deaths had a set price.

London was a global trade hub. Ships still needed unloading. Goods still needed storage. Contracts still needed to be fulfilled. None of that worked if a single blaze could bankrupt everyone on a street.

The idea that changed everything was simple: stop treating fire as divine punishment and start treating it as a calculable risk. Put a price on it. Charge for it. Pay out when it happens.

That shift is the foundation of almost every home or landlord policy sold today.

2. Nicholas Barbon: The Pioneer with a Namesake Problem

Enter Nicholas Barbon, the man with possibly the most internet-worthy name in insurance history.

His father was a hardcore Puritan who reportedly christened him:

“If Jesus Christ had not died for thee thou hadst been damned Barbon.”

You can see why he shortened it to “Nicholas.”

Barbon trained as a doctor but quickly realised there was more money in property. After the fire, London was one giant construction site. He bought leases, put up new brick houses, and generally behaved like an aggressive real estate developer centuries before the phrase existed, a sharp contrast to earlier worlds where medical malpractice laws under Hammurabi tried to regulate what happened when healers caused harm.

Somewhere in all that rubble and scaffolding, Barbon saw the bigger opportunity. People were suddenly terrified of fire. They had seen what one blaze could do. If you could offer them a way to soften that risk, they might pay for it.

In 1680 he founded what became known as the Fire Office. The sales pitch was radical for its time but familiar to us:

- You pay a premium now.

- If your insured house burns, the company pays to rebuild later, up to an agreed value.

- The loss from one fire is shared across many policyholders instead of annihilating one unlucky family.

Barbon turned fire from a personal catastrophe into a shared, predictable cost. That mental shift is what makes mortgages, landlord portfolios, and modern property markets possible. If you follow that line forward, it leads directly to the morbid origins of life insurance, where the value of a human life itself became something you could write into a policy.

3. If You Didn’t Have This Sticker, Your House Burned

A paper policy is useless once flames hit it. So early insurers came up with something tougher: Fire Marks.

These were metal plaques, stamped with the company’s emblem and nailed to the front of your building. Walk down a London street in the decades after the fire and you would see tiny suns, clasped hands, and other symbols staring down from the brickwork. They were early brand logos and early security signs in one.

The marks did three things at once:

- They told the insurer which properties it had promised to cover.

- They acted as advertising to your neighbours.

- They sent a clear message: this building has backup if the worst happens.

Then came the rumour that gives this section its sting. According to popular stories, when a fire broke out, the private brigades would roll up, look for their own company’s mark, and only fight the fire if they saw their logo. Wrong plaque or no plaque, and they would hold back while your house burned.

Reality was a bit more practical. Fires don’t stay politely inside property lines, and letting one uninsured building burn could destroy several insured ones next door. Over time, most insurance brigades would fight any major blaze they reached.

But the perception stuck. No mark meant no priority. The plaque on your wall told the world whether anyone had a financial reason to care if your house caught fire.

4. Insurance Companies Owned the Fire Engines

Here is the part that sounds completely upside down today: for two centuries after the Great Fire, London had no public fire service.

If your house caught fire in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, you shouted for the neighbours and hoped your insurer’s crew turned up in time.

Those crews were not city employees. They worked for the insurance companies. Barbon’s Fire Office was among the first to organise such teams, often recruiting Thames watermen who were used to hard physical work and knew the city well. The companies bought hand-pumped engines, hoses, and ladders, then put their men in uniforms so everyone knew who they worked for.

The motive was simple: every house they managed to save was a claim they didn’t have to pay in full. Firefighting started life as a form of loss prevention, not public service.

As more insurers joined the market, London ended up with a patchwork of rival brigades. Competition was good for customers in one sense: there were more engines, more crews, and more coverage. But fires are not brand loyal, and over time the companies discovered they had to cooperate when a blaze threatened whole blocks.

Eventually, that cooperation turned into something more permanent. By the nineteenth century, it was clear that fire protection worked better as a public utility than as a side project for actuaries. In 1866, London created a publicly funded Metropolitan Fire Brigade, the ancestor of today’s London Fire Brigade. The old private brigades faded away.

Modern firefighters still promote prevention, run inspections, and campaign for safer buildings. That DNA goes straight back to the moment when insurers realised that the cheapest claim is the one that never happens.

5. The Fire Court Chaos That Changed Renting Forever

Now imagine this legal problem.

You are a tenant in 1666. Your lease says you must keep the house in good repair and pay rent on time. Then the Great Fire turns your street into charcoal. The building no longer exists.

Your landlord points at the lease and says, “Pay up.”

You point at the smoking foundations and say, “What house?”

Multiply that by thousands of properties and you have the post-fire mess. Landlords worried that if they paid to rebuild, tenants would march back in on their old terms and effectively get a brand new property for the price of a damaged one. Tenants argued they should not pay rent for a pile of bricks.

Parliament’s solution was drastic. The Fire of London Disputes Act 1666 created a special Fire Court. It sat from 1667 to 1676 and had one job: sort out rebuilding disputes fast.

Judges could:

- Cancel or rewrite leases.

- Divide rebuilding costs between landlords and tenants.

- Unpick complicated ownership and mortgage arrangements.

In plain language, they had the power to override private contracts to keep the city functioning.

Those decisions set early precedents for how the law handles property after major disasters. They also showed something modern readers will recognise from financial crises and pandemic rules: when the survival of a city or economy is at stake, the state can and will change the deal.

A lot of modern landlord-tenant law, and even some modern ideas about disaster relief and rent holidays, has roots in that smoky courtroom.

The Legacy: From Pudding Lane to Your Premiums

Today the insurance industry is worth trillions. It prices everything from coastal floods and wildfires to ransomware attacks. It quietly shapes where we build, how we borrow, and what risks banks and governments will tolerate, sitting alongside other inventions that changed how the world works but often stay invisible until something goes wrong.

But the basic logic behind your home policy was hammered out in burned streets and improvised courtrooms in the 1660s.

- The idea that you can pool risk so one fire does not ruin one family.

- The use of visible signals (like Fire Marks, now replaced by policy documents, inspections, and building standards) to show who is protected.

- The principle that governments may rewrite private contracts after large-scale disasters to keep the system from seizing up.

All of that starts with a bakery in Pudding Lane, a city turned to ash, and a man with a ridiculous name who looked at the ruins and saw a business opportunity.

Next time you roll your eyes at your insurance premium or skim that “buildings and contents” section in your policy, remember this: the alternative, for most of history, was waking up one morning to find your house gone and your only hope a collection plate.

Which of these facts surprised you most? Tell us in the comments — preferably from a house that is fully insured.

Not in any way we’d recognise today. Before 1666, there was no standard system for insuring houses against fire. Losses were treated as “Acts of God” and people relied on charity, loans, or family. The Great Fire exposed how fragile that was and pushed London toward formal property insurance.

Nicholas Barbon was a physician turned property developer who helped rebuild London after the fire. In 1680 he founded the Fire Office, one of the first fire insurance companies in London. His big idea was simple: many people pay small premiums so that no single fire ruins one person completely. That basic model still underpins modern home insurance.

Fire marks were metal plaques fixed to insured buildings to show which company covered them. Early insurance brigades did prioritise their own customers, and the legend says they ignored houses without the “right” mark. In practice they often fought any major fire to stop it spreading, but the message was clear: with no mark, your house was not top of the list.

The Fire Court was set up because thousands of leases and mortgages no longer made sense once the buildings were ash. Tenants technically still owed rent; landlords didn’t want to rebuild without better terms. The court had power to rewrite contracts so rebuilding could go ahead. It became an early model for how the law handles property after major disasters.

The fire pushed London to invent organised fire insurance, private fire brigades, and legal tools for untangling post-disaster property disputes. Those experiments evolved into today’s home insurance policies, public fire services, building regulations, and the idea that governments may intervene in contracts after major catastrophes. Your modern premiums and protections trace back to that four-day inferno in 1666.

Sources and further reading

Museum of London – How the Great Fire created insurance

A clear, reader friendly overview tying the 1666 fire directly to the birth of property insurance and fire marks.https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/blog/how-the-great-fire-of-london-created-insurance/

London Fire Brigade Museum – Early insurance brigades

Explains how insurers owned the first fire engines and ran private brigades before a public fire service existed.https://www.london-fire.gov.uk/museum/london-fire-brigade-history-and-stories/early-insurance-brigades/

Insurance Hall of Fame – Nicholas Barbon

Short, authoritative profile of Barbon as founder of the Fire Office and pioneer of modern fire insurance.https://www.insurancehalloffame.org/nicholas-barbon-simple

UK Parliament – Aftermath of the Great Fire & Fire Court

Parliament’s own page on the Fire of London Disputes Act 1666 and the special court that rewrote leases and property rights.https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/collections/collections-great-fire-1666/aftermath-of-the-great-fire/

London Insurance Market / Insurance Museum – History of fire insurance

Modern insurance sector view of how the Great Fire turned fire cover from a curiosity into an urgent economic tool (good for “industry” angle).

- General history PDF:

https://londoninsurancelife-lmg.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/History-Development-of-Insurance-Industry.pdf