In 1781, a British slave ship called the Zong sailed across the Atlantic with more than 440 enslaved Africans chained in its hold. Weeks later, over 130 of them had been thrown alive into the sea.

When the ship finally reached Jamaica, the owners did something almost unbelievable: they filed an insurance claim for their “lost cargo.” The court case that followed, Gregson v Gilbert, was not a murder trial. It was a commercial dispute over whether the insurers had to pay £30 per head for the people killed. The result was a grotesque incentive:

- Let people die slowly on board? No payout.

- Kill them quickly in the “right” way? You might get your money back.

The Zong massacre shows one of the most extreme examples of law putting a cash value on a human life, part of a long, grim tradition that stretches from Anglo-Saxon wergild compensation tariffs to the way modern courts and insurers still calculate “loss” today.

Museum Fact File

Event: The Zong Massacre (1781)

The Crime: 132+ enslaved Africans deliberately killed for insurance money

The Legal Loophole: “General Average” – treating people as sacrificial cargo

The Result: No one was ever charged with murder

1. The “Human Property” Loophole

In the late 1700s, British marine insurance didn’t recognise enslaved Africans as people. On paper they were listed as “living cargo”, insured like barrels of rum or bales of cotton. Policies valued them at around £30 each, payable if they were lost at sea under certain conditions.

Here was the deadly logic:

- If enslaved people died of disease, malnutrition, or “natural causes”, the owners got nothing. This was considered normal voyage “wastage.”

- If they were thrown overboard in an “emergency” to save the ship and the rest of the cargo, their value could be claimed under a maritime principle called general average.

General average is a centuries-old rule that says: if a captain sacrifices part of the cargo intentionally to save the voyage, everyone with a financial stake must share the loss. It was designed for things like jettisoning barrels in a storm. On the Zong, it was applied to human beings.

The result was a grotesque incentive:

- Let people die slowly on board? No payout.

- Kill them quickly in the “right” way? You might get your money back.

The massacre on the Zong was not a random act of cruelty. It was a business decision made inside that loophole.

2. The Case of the Missing Water

The Zong left the African coast in September 1781, overloaded with more than 440 enslaved Africans and a relatively small crew. The captain, Luke Collingwood, was on his first voyage in command and made serious navigational errors. The ship overshot Jamaica and wandered for weeks, stretching the journey far beyond the usual crossing time.

Disease and exhaustion spread. People on board – both crew and captives – were dying. Collingwood and his officers then claimed they faced a crisis:

- They said the ship was running out of water.

- If the enslaved Africans died of thirst or illness, the insurers owed nothing.

- If they were thrown overboard to save the ship, they counted as a sacrificed cargo loss under general average.

So they began killing people in batches.

- Women and children were reportedly hauled up and pushed through gun ports into the ocean.

- On later days, groups of men were forced over the side, still chained.

- One man fought his way back on board after being thrown overboard, only to be cast into the sea again.

That one detail – a man climbing, dripping, back onto the deck, desperately clinging to life while the crew pushed him away – is the moment the “insurance logic” of the massacre collides with the human reality.

When the Zong finally arrived at Black River, Jamaica, roughly 208 enslaved Africans were still alive. More than 130 had been murdered.

And then came the detail that shattered the captain’s story.

When the remaining supplies were checked, the ship still had hundreds of gallons of fresh water on board. There was also evidence of rainfall during the killing period, which would have allowed the crew to replenish the casks.

The “shortage” used to justify throwing people overboard looks, in hindsight, less like a tragic necessity and more like a carefully constructed excuse for turning a failing voyage into a claimable loss.

3. A Trial About Money, Not Murder

Back in Britain, the ship’s owners did exactly what their paperwork was built for: they sent the bill to the insurers.

They claimed for the value of the enslaved people they had “jettisoned” as cargo. The underwriters led by insurer Thomas Gilbert refused to pay. The owners sued, and the case Gregson v Gilbert began.

Crucially, this was not a criminal trial. No one asked a jury to decide whether 130 people had been unlawfully killed. Instead:

- The case was heard in a commercial court, as a routine marine insurance dispute.

- The first jury actually found in favour of the ship’s owners, accepting that the killings were covered by general average.

- Only when the insurers appealed did the case reach the Court of King’s Bench under Lord Chief Justice Lord Mansfield.

It’s a stark contrast with earlier systems like Hammurabi’s medical malpractice laws, where even ancient codes spelled out brutal penalties when professionals caused harm. On the Zong, the law’s harshness fell entirely on the enslaved, not on the men who ordered them into the sea.

In his comments, Mansfield spelled out the brutal logic of the law:

The situation, he suggested, was “exactly as if horses had been thrown overboard.”

That line has echoed through history. In the eyes of eighteenth-century commercial law, the question was not “Was this mass murder?” but “Was this an insurable sacrifice of property?”

Mansfield eventually ordered a new trial, partly because the evidence about water supplies and navigation undermined the claim of “necessity.” But no second trial on the insurance issue ever took place – and, more importantly:

- No one from the Zong was prosecuted for murder.

- No captain, officer, or owner faced criminal charges for killing more than 130 people.

On the legal record, the Zong massacre survives as a failed insurance claim, not a homicide case.

4. The “General Average” Technicality – From Zong to the Ever Given

The Zong massacre hinged on the maritime rule of general average – a concept that still shapes global shipping today.

In simple terms, general average says:

If the crew intentionally sacrifices part of the ship or cargo to save the voyage from a common danger, everyone with a financial stake must share the loss.

It is meant for choices like:

- Cutting away a mast in a storm

- Flooding a hold to put out a fire

- Throwing cargo overboard to stop a ship capsizing

On the Zong, this rule was twisted into a justification to kill enslaved Africans, classed as “cargo.”

The owners argued:

- The killings were a necessary sacrifice to save the ship and the rest of the cargo.

- Therefore the insurers should pay for each “lost unit” at the insured value.

The insurers argued:

- The supposed emergency was caused by bad navigation and mismanagement.

- The killings were not truly necessary and so were not a valid general average loss.

The principle itself, however, survived.

Did you know?

The same general average rule that was cited in the Zong case was invoked in 2021, when the giant container ship Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal. The ship’s owners declared general average so that cargo owners would share the massive costs of salvage, delays, and legal claims. The legal machinery that once priced enslaved people as cargo still quietly governs how we divide up the bill when global shipping goes wrong.

The mindset behind it turning uncertainty into numbers, and people into units on a risk ledger is the same logic that later fed into the morbid origins of life insurance, where a human body became something you could literally underwrite.

Behind both stories is another familiar name: Lloyd’s of London. What is now the world’s most famous insurance market began as Lloyd’s Coffee House in London, where shipowners, merchants and underwriters met to write exactly these kinds of marine policies including, at the time, policies on slave ships. If you want to see how another disaster helped invent modern insurance, read our piece on 5 wild ways the Great Fire of London invented insurance.

The Zong was not an anomaly in an otherwise humane system. It was an extreme example of what could happen when maritime law, insurance and slavery intersected in a world where human beings were entered as assets on a ledger.

5. The Receipt That Changed the World

What finally made the Zong massacre impossible to ignore was not a confession. It was paperwork.

The owners, in trying to recover their “losses,” left a trail:

- The insurance policy valuing enslaved people as cargo.

- The owners’ claim for those thrown overboard.

- Witness statements and court transcripts describing, in chillingly dry language, the days of killings.

Abolitionists seized on these documents.

Granville Sharp, one of Britain’s most determined anti-slavery campaigners, got hold of the case papers. He wrote letters to officials demanding that the crew be prosecuted for murder, circulated accounts of the massacre, and used the Zong as a flagship example in the growing movement against the slave trade.

Those “receipts” did three powerful things:

- They showed, in the shipowners’ own words, that people had been killed deliberately for financial reasons.

- They exposed the slave trade not just as a moral horror, but as a system of insurance, credit and contracts.

- They provided concrete, quotable evidence for pamphlets, sermons and speeches that reached the British public.

Many of these records survive.

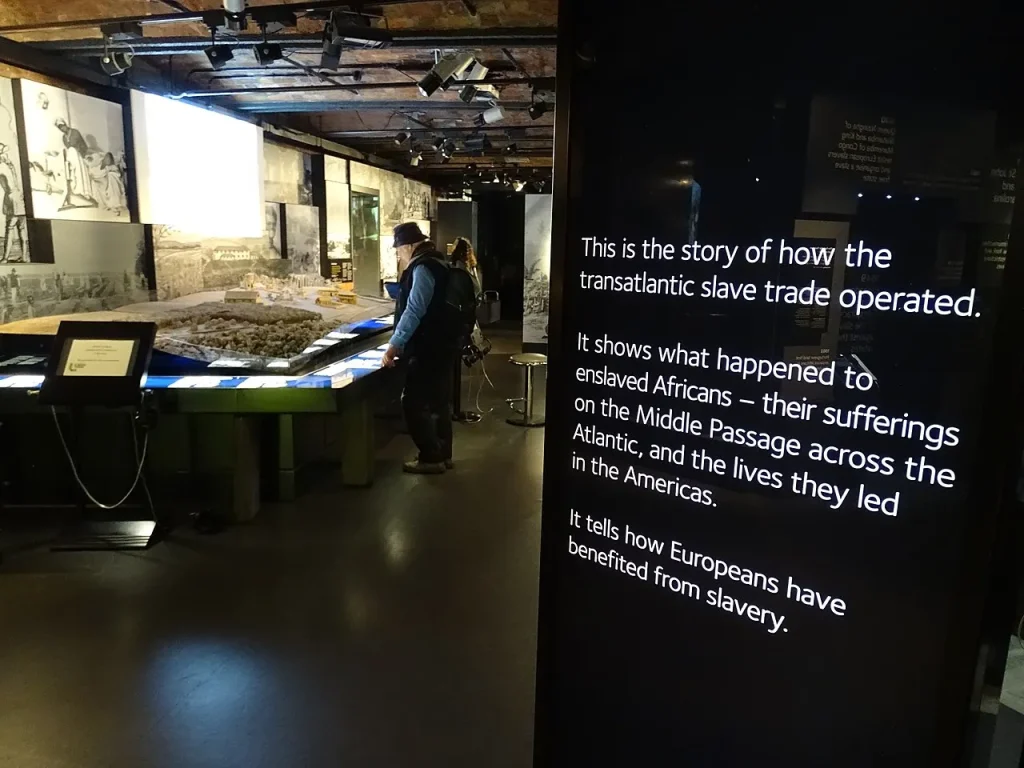

- At the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, you can see documents and case materials that set out how slave voyages were insured and financed.

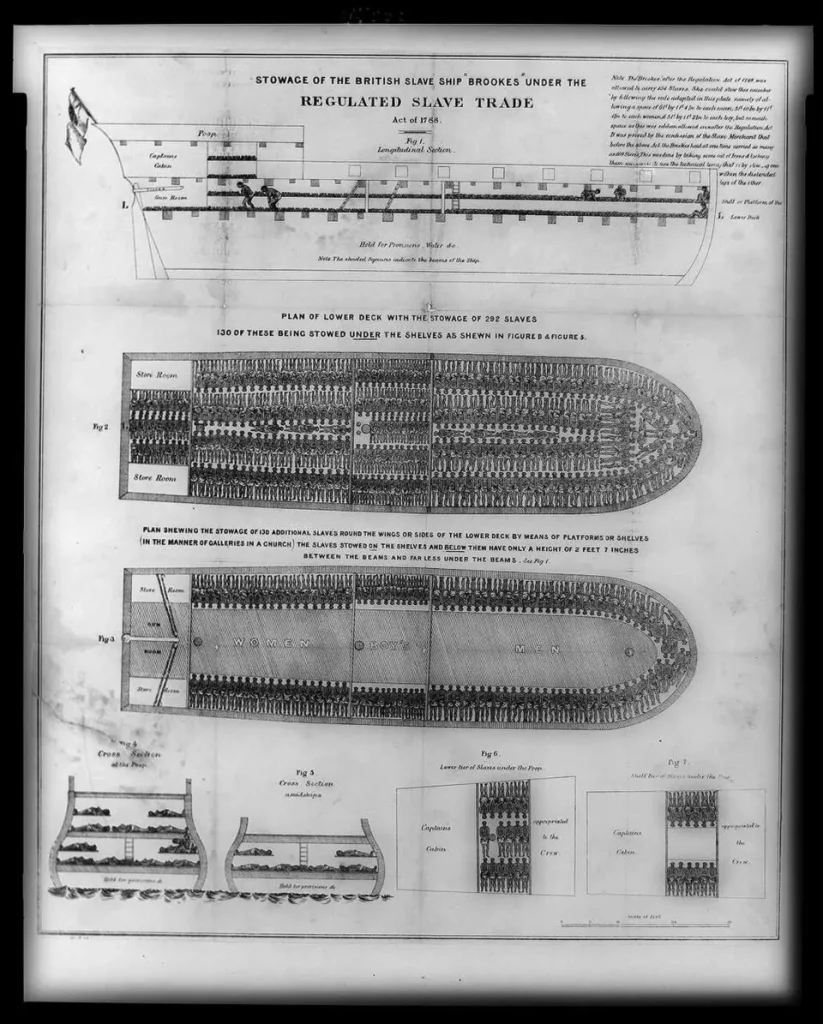

- At the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool, you can see exhibits on the city’s role in the transatlantic slave trade, including maps, ship diagrams and merchant records from the very firms that insured and fitted out ships like the Zong.

The Zong case helped drive public outrage, feeding into the campaign that led to the Slave Trade Act 1807, which ended Britain’s legal participation in the transatlantic trade, and later the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833.

A commercial dispute about an insurance payout became one of the most important pieces of evidence in the long fight to dismantle the trade itself.

Quick-Fire Facts Table

| Fact Category | The Shocking Detail |

|---|---|

| The Payout | Owners tried to claim £30 per person thrown overboard (worth thousands today). |

| The Loophole | Death by disease was not insured, but killing at sea could count as a sacrifice of cargo under general average. |

| Total Victims | Between 132 and 142 enslaved men, women and children were murdered. |

| The Legal Frame | Main case, Gregson v Gilbert, was an insurance dispute, not a murder trial. |

| The Legacy | Fuelled the abolition movement and influenced later limits on slave ship loading and maritime insurance practices. |

The Zong massacre is one of the clearest examples in history of what happens when laThe Zong massacre is one of the clearest examples in history of what happens when law and finance strip people of their personhood:

- Risk is calculated per head.

- Human lives are treated as entries on an insurance schedule.

- A mass killing can pass through court as a technical argument about policy wording.

It also reminds us that some of the most powerful “inventions” in history aren’t machines, but systems – insurance, contracts, credit – that quietly shape who is protected and who can be written off. If you like seeing how these hidden systems changed everything, here are other inventions that remade the world behind the scenes.

The Zong forces us to ask:

When money, law and human life collide, who do our systems actually protect – and who can still be thrown overboard?

Yes. The killings were carried out specifically so the ship’s owners could claim money from their marine insurers. Enslaved Africans were treated as “living cargo”: if they died of disease, the owners got nothing; if they were thrown overboard in an alleged emergency to save the ship, the owners could try to claim their value under maritime insurance rules.

The massacre relied on a maritime principle called general average. This rule says that if part of the cargo is deliberately sacrificed to save the ship and the rest of the cargo, all stakeholders share the loss. On the Zong, enslaved people were listed as cargo, so killing them at sea was framed as a “necessary sacrifice” instead of murder.

Because the case went through a commercial court, not a criminal one. The main trial, Gregson v Gilbert, was about whether the insurers had to pay for the “lost cargo,” not about whether the killings were unlawful. The judge treated the deaths as a question of property and necessity, not homicide. No criminal charges were ever brought against the captain or owners.

Most accounts put the number between 132 and 142 enslaved Africans — men, women, and children — thrown overboard over several days. Many others died earlier in the voyage from disease and the brutal conditions on board, but those deaths were not part of the insurance claim.

The Zong case shows how law and insurance can turn human lives into numbers on a balance sheet. It became a key piece of evidence for abolitionists, helped fuel the campaign to end the British slave trade, and still raises uncomfortable questions about how modern systems price risk, decide who is “covered,” and who can be written off when profit and human life collide.

Sources

Encyclopaedia Britannica – Zong Massacre

Clear overview of the events, timeline and legal context.https://www.britannica.com/event/Zong-massacre

Museum of London – The Zong Massacre Trial

Short, museum-style piece linking the case to London’s legal and insurance history.https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/london-stories/zong-massacre-trial/

National Maritime Museum – Documents Relating to the Ship Zong

Archival description of the original court papers, letters and accounts used by abolitionist Granville Sharp.https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-500960